Interview | The Iranian Left, the Labor Movement, and the Future of Iran

Over the last decade, Iran has been shaken by waves of social upheaval ranging from "Bloody November" to the "Woman, Life, Freedom" uprising. Squeezed between the regime's apparatus of repression and the right-wing monarchist winds in the diaspora, the Iranian Left is attempting to weave a new line of resistance from factories to universities despite all hardships. In this interview, we spoke with Mehdy Toophchi, activist and former board member of the Association of Labor Rights Defenders, about the state of the Iranian Left in exile, the class character of the current protest waves in Iran, and the possibilities for a common liberation for the peoples of the region. Toophchi does not merely offer an analysis; he emphasizes the vital importance of building an internationalist bridge between the Turkish and Iranian working classes.

Can you tell us about yourself? How long have you been living in exile? When were you forced to leave the country?

I played an active role as a labor activist within the socialist movement in Iran and was a former board member of the Association of Labor Rights Defenders. During the nationwide protests in January 2017, I was arrested in Tehran on charges of leading these protests, and I was forced to leave Iran at the end of that year.

What is it like to be a socialist forced to live abroad while continuing the struggle for Iran?

Life in exile and political activity have their own specific characteristics and impose requirements and necessities beyond one's will. Besides the personal and individual problems that surround a person, for a field activist and practical leader who is in constant contact and communication with society and the ranks of social activists, it is like "throwing oneself from the ocean into a small aquarium!" This creates great mental and psychological pressure. Consequently, overcoming this situation and continuing the struggle and action was the first stage of the exile I faced—an experience I was completely foreign to until then. This experience coincided with a period when the labor movement in Iran was heavily involved in struggle and conflict with the government and capitalists, and many of my friends and comrades were under the heaviest security, police, torture, and prison pressures. The obligation to support and defend these activists and socialists imposed a multi-layered and multifaceted conflict on me at the beginning of my life in exile.

Every few years, a wave of action or an uprising breaks out in Iran. It is as if every generation has its own Intifada. Regarding the January 2026 protests, an observation is made about the protesters: a mix of the "Bazaar" (the traditional merchant class), which was once the regime's base, and a secular, semi-political young generation advocating for the regime's collapse even at the cost of the Shah's return. How can we make sense of the crowd currently rebelling in Iran? Did these two groups merge politically? What is the political landscape?

That is absolutely correct. In the last eight years, we have witnessed four national waves of protests and uprisings in Iran, each with its own unique model in terms of participant structure, movement content, and demands, as well as the composition of social, political, and economic strata and classes.

What is certain today is that we are faced with a situation where labor rights, livelihood, economic, cultural, and political demands have widely converged; this is qualitatively different from the movements and uprisings preceding these last four waves and requires special attention.

The point I want to emphasize is that to understand these uprisings, we need a correct and realistic perspective—one that differs significantly from the popular representations by certain segments of the opposition both inside and outside Iran. Paying attention to the objective and material reality of these uprisings makes the observer's perspective more realistic, precise, and concrete. Without understanding this, any analysis or theorizing will inevitably be incomplete and unproductive.

The second and most important issue is the state of society and social movements in the period between each of these uprisings. When we look at the period between the January 2017 uprising and the November 2019 uprising, we clearly see the growth and expansion of labor protests and strikes across the country. During this period, workers and labor unions were in constant struggle and debate against the unbridled privatization policies and the implementation of the Islamic Republic's so-called "economic adjustment" policies; the most prominent examples of this are the strikes of the Haft Tappeh workers and the Ahvaz Steel Company.

The accumulation of this dissatisfaction and reaction finally led to the November 2019 uprising, where the government delivered a new economic shock to society by removing some energy subsidies and increasing gasoline prices. In response to this policy, society poured into the streets en masse, and the regime responded with widespread repression and killings.

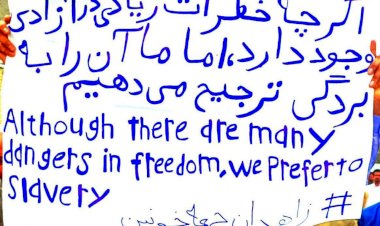

Between the fuel protests of November 2019 (Bloody November) and the 2022 "Woman, Life, Freedom" uprising, we once again witnessed the continuation and expansion of social protests. Teacher and retiree unions went on strike and held street rallies against the privatization of education and the continuation of economic adjustment policies. At the same time, the government's religious and cultural policies against women and youth intensified; this included the intensification of "morality patrols" and the creation of a police and security environment in streets and cities. These violent incidents made society extremely sensitive, and tolerance for such interactions, especially towards women, was minimized.

In such a context, the killing of Mahsa Amini in police custody in Tehran became the spark for a widespread national uprising across Iran; an uprising that lasted more than four months and once again faced violent and widespread repression. After the "Mahsa" uprising, far from changing its policies, the government continued on the same path, plunging society into an even heavier social, political, economic, and livelihood crisis. In recent months, a "direct and widespread attack" on people's lives and livelihoods was carried out by implementing the "economic surgery" policy, which is actually a continuation of the same privatization and structural adjustment policies. As a result, a conflict broke out again between society and these policies, bazaar strikes began, people returned to "street politics," and a new wave of protests formed across the country in January 2026.

Given this situation, and with the lack of a coherent and deep-rooted opposition to represent these various demands on one hand, and the intense media propaganda and promotion work launched by a significant part of the media outside Iran around the "Pahlavi Alternative" on the other, the monarchist movement has effectively gained superiority in the media and symbolic sphere at this point.

The multi-layered and diverse structure of the protesters in these uprisings is clear. We are faced with the presence of different social strata and classes in unprecedented protests. However, reaching a definitive judgment on whether the majority of protesters support Reza Pahlavi or want the return of the monarchy to Iran is not a simple or clear matter due to the lack of organization and stable formations among protesters, as well as the absence of independent, impartial, and transparent media. This requires more detailed analysis and research based on objective data.

You are Azeri. In Iranian Azerbaijan, Azeris who were uncomfortable with the prominence of Monarchists also shouted "Neither Shah nor Mullah" slogans. What is the political mood in a large city like Tabriz? Which political thought is coming to the fore?

As you know, Iran has a very diverse geography of people and cultures, and in recent uprisings, we have seen widespread and consistent participation in different parts of the country. As I mentioned, definitive indicators and field studies are also needed to reach a final judgment on the extent of monarchism's influence or acceptability in Azerbaijan. However, in general and at the level of social reality within Iran, it can be said that there are serious and significant conflicts against this political trend.

In my opinion, in recent uprisings and in the absence of sustainable organizations and formations due to repression, the content of slogans alone does not hold decisive analytical and political significance. But of course, it is still an indicator. My personal experience in participating in spontaneous and self-organized street protests shows that the shouting of any slogan can occasionally attract some of the people on the street without necessarily expressing their deep and stable political leanings.

Furthermore, I must emphasize that this region is not fundamentally different from other parts of Iran. Nationalist groups in Azerbaijan do not enjoy widespread social acceptance and are practically in a state of attrition and passivity. The public atmosphere in Azerbaijani cities, especially in Tabriz, during the recent uprisings is based on unity and solidarity with other cities and regions of the country. Repeated attempts by nationalist movements to fuel separation and conflict with other ethnic groups and the geography of Iran have not achieved significant social success so far.

For example, the slogan "Turks and Persians must be one so that this homeland can develop," heard in Azerbaijani cities, especially Tabriz, during this period, is, in my opinion, a more progressive slogan that clearly opposes the discourse and propaganda of this nationalist segment.

Finally, another important point about Azerbaijan: given the geographical location of this region, the size of its cities, and the prominent role of Azerbaijan's commercial and industrial capitalism in the Iranian economy, there are deep social, economic, and cultural ties with other parts of the country, making simple separation or isolation impossible. A clear example of this is the Tehran bazaar, known for the distinct presence and role of Turkish and Azeri merchants who traditionally have ties with the system as well. Moreover, especially in the context of economic sanctions and given Azerbaijan's role in the communication corridor with Turkey, Iran's financial and commercial bourgeoisie has deep and structural ties with Azeri merchants and businesspeople.

Do you think there are foundations for an ethnic fragmentation in Iran?

Iran's social and human geography is extremely diverse and consists of numerous ethnic groups and subcultures. By this diversity, I do not just mean ethnic or tribal diversity; on the contrary, even within each of these ethnic groups and tribes, we encounter a complex, heterogeneous, and sometimes contradictory plurality. For example, in the Azerbaijan region of Iran, we witness various subcultures that show broad overlaps in some cases, while in others, we encounter cultural and social differences or even conflicts. Bringing up this issue emphasizes the need to recognize ethnic, tribal, and cultural diversity in Iran.

At the same time, this diversity has led to a kind of continuity and intertwining in social relations and connections through a historical common destiny in the Iranian geography; this continuity has also objectively and materially contributed to the cultural and social richness of society. This reality has formed and continues its existence independently of the will and policies of the Islamic Republic and the rule of the Shia religion; moreover, in a situation where the government has always tried to divide society by fueling divisions and conflicts.

Nevertheless, ethnic, tribal, and cultural demands have always been among the most important social demands and desires in Iran and have manifested themselves in various ways in various movements. Despite this, I do not see a high risk of serious ethnic and geographical conflicts in Iran in the short term; however, given the unstable situation in the Middle East, the possibility and potential risk of such scenarios should not be completely ignored.

Historical experience shows that these ethnic groups and social groups have repeatedly passed through difficult and critical tests; tests that could have led to bloody conflicts were successfully passed by relying on social solidarity and a sense of common destiny in practice. Furthermore, in many crises and problems where the government avoided taking responsibility, society and various social groups came together and helped each other, managing to control these crises in the most social way. The earthquake in Turkey on February 6, where you suffered great losses, also hit us; followed by floods. In all of these, the state remained helpless and did nothing. Intervention was made by people from different regions forming social solidarity networks. Such a culture exists in Iran. Taking this into account, if we take the starting point of the analysis as the real and concrete relations in Iranian society, the possibility of widespread ethnic and geographical conflicts is minimal, at least under current conditions—unless, of course, it is subjected to a special hostility or forced division by the system.

On the other hand, if we base the analysis not on real and lived social relations but on the narratives and claims of nationalist groups or emerging collectives in search of identity, a completely different picture emerges. In these narratives, the impression is given that Iran is already fragmented and society is unaware of this reality; this narrative is a product of the ideological projections and political needs of these movements rather than being based on objective and field facts.

What is the situation of the Left in Iran? Are there conditions to struggle within the country? What kind of roles do you think the Left might have played in the recent actions?

The Left movement, which has a deep-rooted history in Iran, has been one of the most influential and decisive dynamics of modern Iranian history in the last fifty years; it has established deep ties with society and revolutionary movements in regional countries. However, in the last few decades, the Left movement has faced serious problems stemming from both internal dynamics and external factors. These problems have resulted, on one hand, from the post-modern ideological transformations experienced by the global Left, and on the other hand, from the severe repression, security-oriented policies, and harsh police interventions applied by the Islamic Republic against Leftist and revolutionary structures.

The movement that began with the demand for autonomy in Kurdish regions immediately after the 1979 Revolution was met with a major military operation by the Islamic Republic's army and the Revolutionary Guards. Specifically, the years 1360-1363 (1981-1984) were a period when "urban wars" were experienced in the region and the state established full control. However, from the mid-1980s onwards, and especially after the emergence of the government's "structural adjustment" and economic policies, groups and circles of Leftists and supporters of the Left began working in various sectors.

In this process, the unions of the Tehran Bus Company (Sherkat-e Vahed) and the Haft Tappeh Sugar Cane Workers were restructured. In universities, various groups formed by students from different Leftist and revolutionary wings, such as "Students Seeking Freedom and Equality" (Daneshcuyan-e Azadi-hah va Barabar-talab), began to operate. While this activity had a deep impact on academic circles, it also brought with it the regime's intense security pressure, mass arrests, and forced confessions.

We have witnessed the deep impact the Left movement has left on the intellectual field, especially through translated and compiled literature. However, despite this cultural accumulation, the Left has not yet been able to overcome its mentioned structural weaknesses; this situation creates a serious vulnerability in terms of both organizational continuity and social ties. In contrast, socialist activists and the Left movement took on a key role in recent social explosions, putting all their prestige on the line. Especially in the Dey 1396 (January 2018) uprising and the subsequent Mahsa (Jina) Amini movement, Leftist women activists had a decisive influence both at the discursive level and in street activism.

The Iranian labor movement has managed to raise a new and competent generation of union activists thanks to the deep ties it has established with production centers in the last five years. Despite this, the movement has not been able to overcome its chronic weakness regarding socialist organization and institutionalization. Especially in the post-October 7 process, with the escalation of military tension between Iran and Israel and the subsequent internal pressures, socialist activists both inside and in exile entered a spiral of great confusion and pressure.

The multi-layered and heterogeneous mass structure in the January 2026 uprising partially opened the Left's current credibility and strategies to debate. The passive stance displayed by the Left created great question marks both in the eyes of ordinary citizens and radical socialist cadres. Of course, the financial power of right-wing and bourgeois currents and media propaganda's share in fueling the anti-Left wave in society cannot be denied. But the truth is; the Left movement is faced with serious objective and material obstacles it has not yet answered or produced solutions for.

In my opinion, for the Left movement to regain its historical position, it is of vital importance to break away from the dogmatic traditions of the past and resolutely adopt an independent, class-oriented, and socialist politics. We need a fundamental "Renaissance" in both discourse and practice. Only with this approach can the socialist movement in Iran brave these challenges and offer society a real alternative for a free and egalitarian future.

There is a wide Iranian diaspora scattered all over the world. During the solidarity actions organized this time, a different scene emerged compared to the Mahsa Amini protests: tensions occurred between Shah supporters and the Left. We also didn't see actions as large and widespread as those in the Amini protests. How did this wave of rebellion play out among Iranian immigrants?

The period we are in displays a quite different character from the rising phase of the "Mahsa Amini" movement. The main reason for this difference is the monarchist dominance in the media field and the prominence of right-wing and bourgeois forces in the diaspora. As is known, Reza Pahlavi tried to play a decisive role in this process with his calls for the protests on January 8-9.

In recent years, comprehensive and high-budget media campaigns have been carried out, especially influencing the Iranian diaspora. Behind the activity we witness in demonstrations abroad today lies this strategic fortification. The role played by Israel in spreading this propaganda is also quite critical; for many media outlets close to the Israeli government are polishing Reza Pahlavi and the monarchy movement as an alternative to the current regime. These campaigns largely serve the interests of the Netanyahu government. Specifically, Netanyahu's highlighting of Reza Pahlavi as a figure during periods of tension with Iran has made him, in a sense, an apparatus of the "soft war" Israel is waging against the Islamic Republic.

When all these factors come together, Reza Pahlavi and the monarchist movement have established a hegemonic superiority in the media and the diaspora. This structure plays a dominant role today by exhibiting a totalitarian tendency in the opposition wing outside Iran.

In various parts of the world, Leftist Iranians carried out actions with strong anti-imperialist veins, emphasizing labor and freedom, without allowing the Shah's flag to be unfurled. However, of course, their impact remained partial. Why would the world media choose to broadcast this? We did our best to strengthen this initiative across Europe, especially in Germany, and we were successful. A similar Leftist action was achieved in Canada. However, in many places, encounters ranging from political to physical tensions occurred between Monarchists and Leftists. Monarchists were encouraged to play an incredibly aggressive and dominant role in every sense. Still, socialist Iranians carry serious potential in terms of numbers and organizational capacity. The important thing is to be able to turn this into an organization without allowing for sectarianism.

What can be done for solidarity with the people of Iran?

This issue is of great importance. First of all, knowing that you have been closely following the labor movement and the socialist struggle in Iran for the eight years since the January 2018 uprising, I would like to offer my special thanks to your movement and the Turkish labor movement for offering unwavering support to Iranian socialists. Despite all the political complexities of the region and Iran, the positions you have taken have always been consistent and resolute with the radical Left movement in Iran.

The solidarity of socialist movements and the continuity of regional struggle is a strategically critical issue. In addition to your political support, your steps towards the correct introduction of the movement in Iran to Turkish society will both strengthen the resistance within Iran and gain broad support from the Turkish public, ensuring the correct development of the internationalist consciousness of the Turkish working class.

We are completely ready to deepen our relations with the labor movement and the radical Left in Turkey; we can reinforce mutual solidarity through political panels, discursive conferences, and forums. I believe that the fate of the Iranian and Turkish working classes is largely common and their interests are inseparable. I hope to produce common policies on the path to raising the class struggle and realizing the liberation ideals of the working class.

The peoples and laborers of the region have no other possibility for salvation. This alternative can only be built on these foundations and around a socialist program.