Rosa Luxemburg: Struggle and Ideas - V.U Arslan

Rosa Luxemburg, the unforgettable leader and theorist of workers’ revolutions, was born 150 years ago* in Poland as the fifth and youngest child of a well-off and open-minded Jewish family. (1871) In the year Rosa was born, the workers of Paris went out to conquer the sky and organized the Paris Commune. 48 years after this tremendous experience, Rosa would die at the head of another workers’ revolution, where the fate of the entire world and future generations was determined.

The family environment of little Rosa, who was lame due to an illness she had suffered in her childhood, was warm and affectionate. However, the socio-political climate in the land where she was born was quite harsh. Political radicalism, which was not uncommon in Poland, where national and class reactions intersected, attracted not only the youth but also state oppression. The young leaders of the Proletariat Party, which Rosa joined when she was only 15, were destined to die on the gallows. On the other hand, Polish patriotism, which had developed against the Russian and German occupation and had always been strong, had become quite reactionary. The workers' movement was growing stronger, and the sphere of influence of Marxism was expanding. In this environment, Rosa, who had chosen revolutionism at a young age, participated in the organization of a general strike coming under the radar of the political police, and went to Switzerland at the age of 18 to receive a university education.

Rosa, who participated in the political work and efforts of the refugees from Tsarist Russia in Switzerland, took a stand against Polish nationalism. Together with her closest comrade Leo Jogiches, she set out to organize the Social Democratic Party of the Kingdom of Poland and Lithuania. Social democrat was a general name used by Marxist parties, and it was based on the workers' movement in those years. Jogiches was a talented organizer, and Rosa was an effective spokesperson. Although the strong emotional bond between the two eventually broke down, they remained comrades until the end and embraced death together as leaders of the Spartacist Uprising.

The Fight Against Revisionism

Rosa moved to Germany, the center of class struggle, in 1898. The German Social Democratic Party (SPD) was the center party of the 2nd International with hundreds of thousands of members and millions of workers’ support. However, over the years, it was gradually moving away from being the revolutionary party of the working class under the influence of the labor aristocracy (party and union bureaucrats, parliamentarians, and such high-level politicians) that was growing stronger within it. Rosa would become the leader of the party's left wing, which opposed this reformist shift. The pamphlet Reform or Revolution, which she wrote for her discussions with the revisionist movement led by Bernstein, is still relevant as a very solid response.

Rosa became the voice of revolutionary proletarian internationalism in the struggle against the SPD’s slide into reformism, its integration into the bourgeois system, and its backing up into the nationalist-militarist state apparatus. On the other hand, Rosa held back from organizing her left faction within the SPD for many years. The theoretical background of this holdback lies in the question of the working class and the revolutionary party. It is possible to trace this debate in Rosa’s pamphlet titled Organizational Questions of the Russian Social Democracy, written in 1904. In this text, Rosa joins the debate between the Bolsheviks and the Mensheviks and attacks Lenin’s concept of a strictly centralized, vanguard party. To her, such a party would be nothing other than Lenin’s personal dictatorship and would seek to take the working class under its tutelage. With such a perspective, we tragically shouldn’t wonder why Rosa embarked on a separate political organization under her own leadership in Germany at a very late stage.

Theory of Revolutionary Party

What Rosa put forward as an alternative was the power, creativity, and revolutionism of the working class’s grassroots pressure. The working class had the ability to learn from its mistakes and correct them. The idea of centralism emphasized by Lenin did not ring well with Rosa, who was struggling with the bureaucratic inertia of the SPD leadership. But in this way, Rosa would have confined herself to the limits of spontaneity. Accordingly, the party had to be a broad-based, democratic, absolute mass organization that included the different tendencies of the working class and identified fully with the class. Although the source of this design was Marx and Engels, political parties were still in their infancy in their time. However, the international experiences of the workers’ movement would prove that the spontaneous workers’ movement would fail to overcome the reformist parties and the trade union bureaucracy, wouldn’t be able to counter the maneuvers of the bourgeoisie and the labor aristocrats, and would be completely inadequate to take power. Moreover, it was an arbitrary interpretation that a broad party would be more democratic. On the contrary, broad parties with passive membership were more likely to allow bureaucratic tendencies to take hold, and “large parties” that brought together disparate factions in the name of pluralism were more likely to develop bureaucratic factions and intrigue. As a result, Rosa tragically came to establish his own organization, the Spartacist League, very late, due to his mistakes in party theory.

Mass Strike

Rosa greeted the 1905 Revolution in Russia with great enthusiasm. She found in the revolution the expression of the working class’ capacity for independent action, which she had so much emphasized. The mass strike, which had manifested itself for the first time in history, was fascinating. As the left wing of the SPD, she proposed the mass strike for the proletarian revolution in her book The Mass Strike, the Political Party and the Trade Unions. The mass strike was an antidote to bureaucratic inertia and integration into the system, a unification of economic and political demands, and a fusion of daily and long-term demands. By 1910, she had fallen out with Kautsky, the leader of the SPD’s central wing, who supposedly defended orthodox Marxism against revisionism. Kautsky had already given in to a moderate, state-respecting, and electoral policy.

Capital Accumulation

As a Marxist economist, Rosa focused on his studies on imperialism. In her book The Accumulation of Capital, which she wrote in 1913, she argued that the capitalist economy would not be able to achieve profitability and would collapse without spreading to social forms that were not yet capitalist. Imperialism is a competitive struggle for the takeover of these peripheral markets by developed countries. Ultimately, when the end of the spread of capitalism comes, the collapse of the system will occur. But Rosa was not heralding the inevitable victory of socialism in a fatalistic way. She explained the meaning of her slogan, “Socialism or Barbarism” as follows. “either the triumph of imperialism and the collapse of all civilization as in ancient Rome, depopulation, desolation, degeneration – a great cemetery. Or the victory of socialism, that means the conscious active struggle of the international proletariat against imperialism and its method of war.”

Rosa and the October Revolution

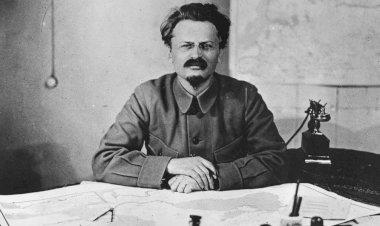

Rosa was imprisoned when she opposed the imperialist war. The SPD had approved war credits in the parliament and thrown the working class into the imperialist meat grinder. Rosa began to organize the Spartacus League in the face of the betrayal of social democracy and was imprisoned. She would be kept in prison throughout the war. She enthusiastically welcomed the October Revolution, which she heard about while in prison; she offered her support and sympathy to Lenin, Trotsky, and the Bolsheviks. On the other hand, she criticized the Bolsheviks on the land issue, the question of nations, and socialist democracy. The Bolsheviks had created a petty-bourgeois layer hostile to the revolution by distributing land to the peasants, made concessions to the nationalists by realizing the right of nations to self-determination, and suppressed other socialist parties (Mensheviks and Narodnik-SRs).

The Bolsheviks responded to Rosa by stating that they could not suppress the oppressed nations suppressed by Tsarism as an external force; that they could create a worker-peasant alliance only by distributing land to the peasants, that the revolution could not survive without this alliance; that the so-called socialist parties, which were considered components of socialist democracy, were in favor of unity with the liberal bourgeoisie, opposed to the socialist revolution, and that the conditions of civil war had to be observed.

The Spartacist Uprising

When Rosa was released in 1918, the German Emperor had fallen and the country was on the verge of a socialist revolution. Armed soldiers and workers were organizing through their own councils and demanding that power be transferred to the councils. On the other hand, just as Lenin had pointed out, there was a huge leadership problem. No mechanism would provide coordination between workers in different German states. The KPD (Spartakists), which had recently taken the name German Communist Party after being inspired by the Bolsheviks, had partial power in Berlin but was completely isolated from other critical cities and industrial areas. The working class was still loyal to the SPD and the USPD, which had stirred away from the former to the left but was oscillating between revolutionism and reformism. The KPD, on the other hand, may have had great potential and seemed certain to grow rapidly, and indeed it did in the months and years that followed, but at the dawn of the German Revolution, the KPD was still very inadequate. As a result of a provocation by the bourgeoisie and the social democrat SPD in its service, the KPD took up arms in an early uprising. Rosa was aware that this was a very premature attempt, but the KPD, which had not been able to establish discipline and organizational functioning, launched the Spartacist Uprising.

The Loss of Leaders

The terrible imperialist war and the October Revolution of 1917 turned the entire world into an arena where the propertied classes and the working class fought a life-and-death struggle. The loss of revolutionary leaders in this fierce struggle in almost every country had serious consequences. Leadership is always decisive, but the situation is much more decisive for the oppressed class. Due to its deprivation under the conditions of capitalist exploitation and its economic and political subjugation, the working class cannot easily fill the void of its revolutionary leaders. Many examples can be given on this subject, the first names that come to mind are the dramatic consequences of the early deaths of Mustafa Suphi and Lenin.

The murder of Rosa and Karl Liebknecht was also a huge turning point. Germany, which was the decisive country for the World Revolution and therefore for the history of the world and the future of the next generations, would experience revolutionary situations after 1919, but the German working class and communists had lost their leaders and the next revolutionary opportunities would be missed. The world revolution was atrophied, the Soviet Union was devastated by imperialist attacks, isolated from the rest of the world, and, unable to heal the wounds it had suffered, sank into bureaucratic corruption.

In conclusion, there is still much to learn from Rosa today. Her struggle against the labor aristocracy, chauvinism, reformism, and bureaucratic inertia remains relevant today with all its burning intensity. Rosa’s devotion to the action of the working class, her ardent internationalism, and her intransigence with the system continue to light our path today.

*The original text was published in 30 March 2021