AfD Victory in Germany: How was Far Right’s Path Cleared? - Emre Güntekin

This Sunday, AfD (Alternative for Germany) has achieved significant success in the elections held in Germany’s states of Thuringia and Saxony, being the first far right party to win an election since World War II. There are many references present in the European press to the Nazis’ electoral victory in Thuringia from 1924. AfD came in first at Thuringia with 33% of the votes, while coming in second to the Christian Democratic Party (CDU) at Saxony with 30% of the voters. BSW (Bündnis Sahra Wagenknecht – Sahra Wagenknecht Alliance), founded in September of last year and led by Sahra Wagenknecht, who broke away from Die Linke (The Left Party), came in third at both states. BSW, received 15.8% of the votes in Thuringia and 12% of the votes in Saxony.

Although the initial statements coming from the ruling social democracy indicate that this had a “shocking effect”, there is no doubt the current result was a foregone conclusion. In Germany, as in Europe in general, the ability of center-right and center-left actors to persuade the masses is dwindling. In both states, the votes received by the German Social Democratic Party (SPD), the Greens and the Free Democratic Party (FPD), which form the ruling coalition, show that the voters choose to penalize these parties.

Ruling parties have little they can do in the face AfD’s rise, in fact they can’t go further than calling out the parties that stood out in the election results. After the results were announced, Chancellor Scholz chose to address the other parties by saying, “All democratic parties must form stable governments that do not include far-right extremists. Our country cannot and should not get used to these results. The AfD is harming Germany. It is weakening the economy, dividing the society and destroying our country’s reputation.” Can this stop the rise of extreme-right? Or rather, can those who are the source of the problem, find a solution as they did in France. They can of course form an alliance without AfD in Saxony and Thuringia with a little help from the trickery of bourgeois politics, again just as in France; but the far-right now has a social reality, and it is against the nature of things to think that this reality will disappear without changing the current conditions and actors.

Therefore, there is no point in being shocked by the rise of far-right in the central countries of Europe, especially in Germany. At this point names like Björn Hacke, who was tried twice for using Nazi slogans, appear as a safer option than the supposedly respectable and “democratic” bourgeois politicians who have been have been harassing workers with neoliberal attacks and instigating imperialist wars for years.

AfD’s rise has been pushing traditional parties to use their own rhetoric in questions such as the refugee problem, which the far right likes to butter its bread with, while also accelerating the right-wing shift in society. Even Sahra Wagenknecht, who won her own election victory by coming in third, did not shy away from becoming part of this campaign from the left. The attack by a Syrian member of ISIS in Solingen on August 23, which resulted in the deaths of 3 people and the injuries of 8, reignited the debate on the immigration issue.

Neoliberalism is deadlocked in almost every sense. A survey in Germany shows that people think the biggest problems facing society are the refugee problem, energy prices, war and the economy; all these are interconnected. As Germany goes through a period where even its iconic brand Volkswagen is considering downsizing by closing factories in the country, the belief that parties such as the SPD and CDU, which have so far been the flag bearers of neoliberal policies, and “left” actors such as the Greens and Die Linke, which have occasionally joined them in federal and regional coalitions, cannot produce solutions to the current problems workers face is deepening.

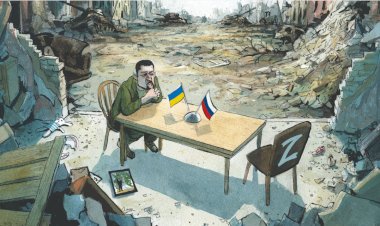

As seen in the state elections, international issues such as Ukraine and Palestine are now among the dominant issues in Germany’s domestic politics and play a decisive role in the elections. The AfD openly opposes Germany’s weight in favor of the Zelensky regime on the Ukraine issue and the military support it’s been providing. Germany is the country that provides the biggest arms support to Ukraine behind the US. When Zelensky visited the German parliament in June, MPs from both parties protested and walked out of the parliament. Moreover, the current coalition has shown that it has prioritized protecting the interests of the NATO bloc within the imperialist competition by launching the largest arms program in Germany since World War II. In the collapse of the parties forming the ruling coalition, the fact that they have been giving a blank check for the genocide against the Palestinian people and violently suppressing anti-Israeli protests are important factor. Indeed, resorting to the shame of the Nazi past and connecting every action of solidarity with Palestine to anti-Semitism does not work on the people; on the contrary, Israel’s reckless genocide in the Middle East and the German ruling class being one of the most ardent supporters of Zionism just fuels the fire.

As a result of all this, the shift towards the AfD, especially among the younger generation and poor working people, has become even more evident in this election. According to exit polls, 31 percent of voters aged 18-24 in Saxony, 37 percent of voters aged 18-24 in Thuringia and 50 percent of low-income voters living in these states voted for the AfD.

It is also striking that both states in which AfD won are within the borders of former East Germany. Although Germany physically reunited after the collapse of the Berlin Wall, societal conditions that keep the wall in spirits remain. The collapse of the wall was to bring blessings of the free world and unlimited liberty to the East which has been living under the oppression of Stalinism for over 40 years. But in the passing decades, neoliberal capitalism has brought nothing but unemployment and poverty to the people of East Germany. Economic inequality between the two sites had not been able to close. At the start of 2010’s, rising discontent in the East was an important reason for Die Linke’s rise in German politics. However, Die Linke’s prioritization of identity politics over class concerns, confinement of its policies to the ballot box instead of shouldering the backlash on the streets, and signing of practices such as privatizations, layoffs in the public sector, and wage freezes in the states where it was a coalition partner, eroded its base in the East. As a result, Die Linke was no longer any different from other bourgeois parties. Now, this gap is being filled by Sahra Wagenknecht, a left-wing populist who broke away from the AfD and Die Linke in the East and highlighted her anti-immigration stance. The far-right, in particular, frequently puts forward the argument that the people living in the East remain under the tutelage of the economically developed West, and here it finds one of the grounds for the polarization it needs.

With the federal elections in Germany just around the corner, the AfD’s success has set off alarm bells. At this point, bourgeois parties have no means to build a wall against this, what the future will hold depends on the attitude of the working class in Germany.